Programming an online multiplayer game is fun! Why, because programming is fun, especially in Rust. Not convinced? Let me show you.

In this post, I will start to talk about the exciting technical stuff around Paddlers. If you haven’t read my other posts (#0, #1, #2), Paddlers is a game in which your goal is to make ducks happy. As of recently, I also have an online live-demo where you can look around and see the current progress. (You can log in using a test user: Username: Tester, password: 1) Just don’t expect too much, it is not a playable game, yet.

Paddland, the world in which the game plays, is a colorful place to relax and have fun. And today, I show you how building this is also fun, using Rust, WebAssembly, and some good old creative freedom to glue everything together.

You might say that programming is boring and only playing games is fun. But you see, if my goal was only to build a fun game, I wouldn’t have started building a distributed system of servers and clients. Instead, I would have chosen something more realistic. Something that might actually be complete one day. But that would be boring to program. And upon completion, it would just be some other game that nobody cares about. After all, I’m just a young man goofing around, without any expertise in game-design, graphics, or story-telling.

So, the main motivation for me to work on Paddlers is not the final game. Instead, I want to have some fun while also acquiring new skills.

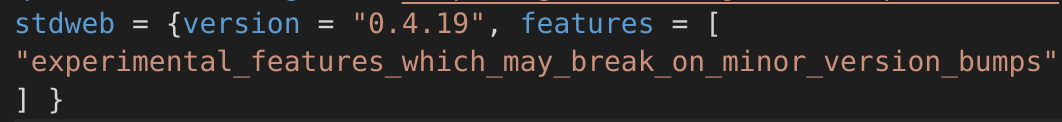

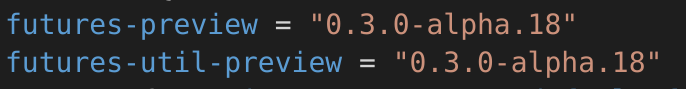

This mind-set allows me to pick the tools that are most engaging for me, rather than always taking the most economic path towards a professional solution. For example, I am using a bunch of unstable rust libraries (also called crates in Rust’s parlance) like these:

Crate dependencies in Paddlers frontend code

Crate dependencies in Paddlers frontend code

Imagine these dependencies in an e-banking software you just shipped. How much fun is that? Not very. But for me, it doesn’t matter. I need these dependencies because I want to use WebAssembly, which is kind of new and hence doesn’t have stable support everywhere.

But enough introduction and description, let us have a technical look at the things I have built so far for Paddlers.

Service Overview

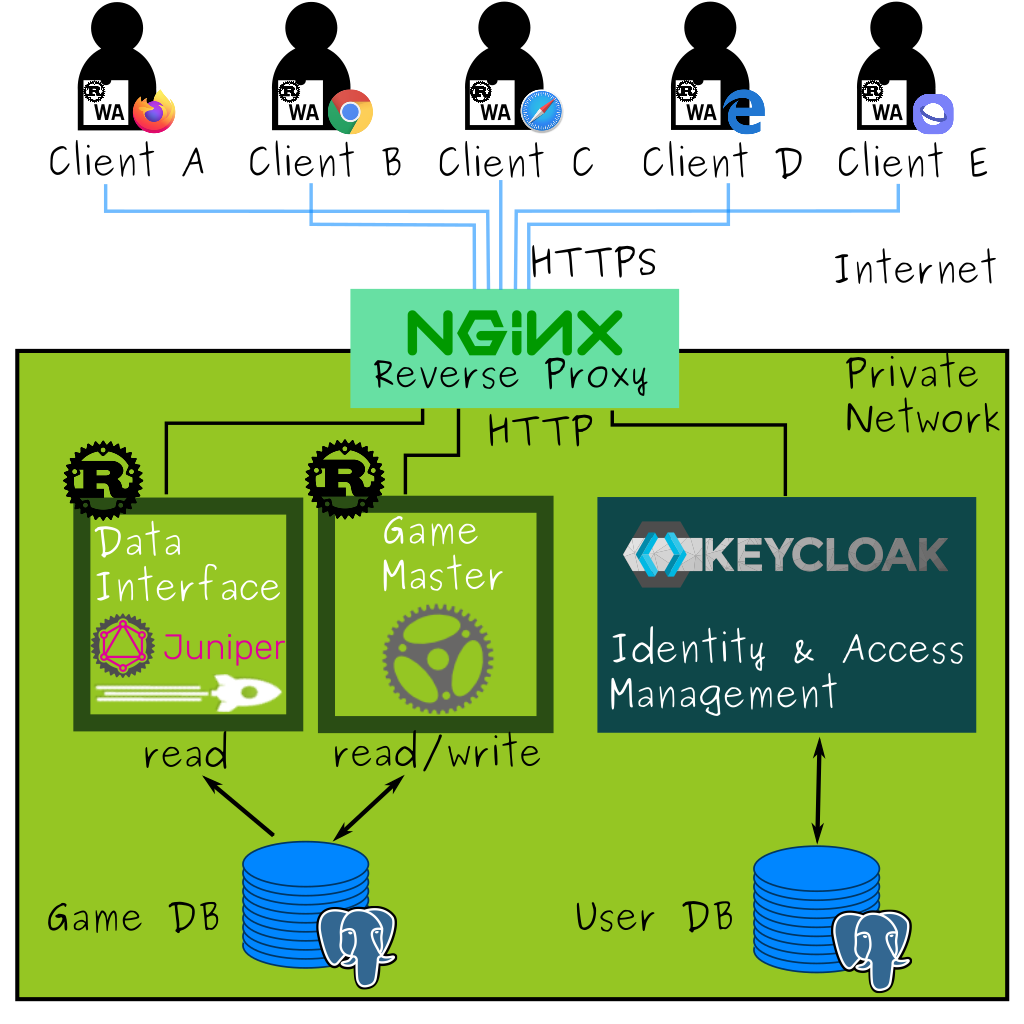

What I call the Paddlers network is currently embodied by a distributed systems of 7 different node types. One node type, the client nodes, runs in the player’s browser. It is written in Rust and compiles to WebAssembly (Wasm). The other six node types are different backend services hosted in separate docker images. The topology looks something like this.

For the backend, you can see that there is an NGINX reverse-proxy with SSL termination as the single entry-point to the server.

Behind this, there is a Keycloak application server running in a JVM in its own docker container. The database providing persistent storage is again in another container, in this case running the standard Postgres image.

Finally, the core of the game backend consists of three node types. One of them is another Postgres image and the other two are custom docker images running custom Rust applications.

If you like buzzwords, you can call this a micro-service architecture. Others will say it’s just a client-server architecture. In reality, I think it is somewhere in between.

I allocated tasks to services with the idea that I want to avoid data-sharing as much as possible since it always increases complexity in distributed systems. To be frank, though, the dominant reason why services happen to be distributed in this manner is my gut feeling that I’ve had on the day when I decided. And if I ever feel like changing it in the future, then I will simply change it again. Isn’t hobby-programming a cool thing?

Software overview

All right, next I talk a bit more about the three nodes that I’ve programmed myself. I will quickly go over them to name-drop a few incredibly useful open-source projects that I’ve had the pleasure to meet in the process.

Frontend Client

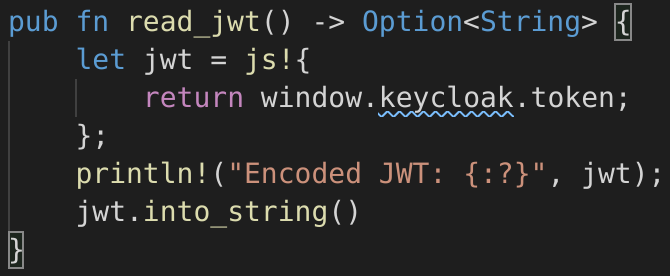

The Wasm client is built using stdweb, one of the two most popular crates providing bindings for the web. (The other one would be wasm-bindgen). Thanks to the awesome people over there, I can write and compile Rust code like this:

The above code snippet is compiled as Rust code. But it has some fancy in-line JavaScript code, wrapped in the js!{} macro call.

With that, it can directly read a JWT user authentication token from the keycloak client, which is an external JavaScript library.

Inside such a macro, we can write arbitrary JavaScript code that will be executed by the browser. Isn’t that amazing? Also, the provided integration is really convenient. Notice how the return value of the above function is a plain old owned Option<String> type that can be further processed by Rust code.

Furthermore, the call to println!() actually prints to the browser’s web developer console while applying Rust’s usual formatting tools.

But let’s defer the detailed discussion about Wasm to another day. Clearly, it is awesome enough that it deserves its own blog post at some point in the future.

Besides stdweb, there are three more important crates for the client code that I want to talk about. Quicksilver, Specs, and graphql_client.

Quicksilver is a framework that combines a bunch of tools to make window creation and drawing on it platform-agnostic. The idea is that games can then render in a browser and natively with the same code, completely portable.

Running my code natively never really was a priority for me and indeed my networking code right now only runs in the browser. I only started using quicksilver because there is barely any frameworks running on the web.

Although it is fairly minimal, quicksilver helped me a lot to get started without bothering myself from the very beginning about WebGL and asset loading.

Unfortunately, I had eventually been forced to fork the crate and use my own branch since adding mobile support did not fit in quicksilver’s road-map at the time. Still, I think quicksilver has been a good choice for me, though. It’s easy to use, well-documented and the maintainer is active and friendly.

Specs

Specs is a recursive acronym for Specs Parallel ECS. It is the most advanced and best-maintained Entity Component System that I could find in Rust and I always wanted to use an ECS in one of my projects to learn about this software pattern.

Specs is also well-documented and I like using it a lot. However, if I had to start over again, I would probably consider building my own ECS-like framework that fits the single-threaded environment in the JavaScript-world better. After all, SPECS has parallel in the name and it shouldn’t surprise you that its focus is on enabling efficient multi-threaded execution.

But to be honest, Specs has everything I need and more. The only benefit of a custom solution that I can think of right now would be that my shared resources wouldn’t need to implement Send, which is Rust’s way of telling the compiler that a structure can be sent between threads safely.

graphql_client

Graphql_client makes it easy to create GraphQL queries that can be sent over HTTP and it helps to parse the responses. I only have to give it the GraphQL interface and query definitions in standardized GraphQL syntax and then graphql_client generates the required structs and methods.

The HTTP requests themselves are sent as JavaScript XMLHttpRequest which is controlled by Rust code. For this, I did not need any further support other then stdweb. To deal with the asynchronous network calls, JavaScript promises are wrapped by Rust futures that can be polled.

Data interface

Moving on to the server-side of things, the first node is called data interface. This is where the backend of the GraphQL interface sits. It presents an abstract view of the game database, defining a graph-like structure between different entities. Behind this sits a PostgreSQL database that stores these entities. But the database implementation could be replaced anytime, without changing the GraphQL interface presented to the client.

The client can send requests to the data interface node when it wants to read data. Thanks to GraphQL, it can specify in each request which fields exactly should be included in the response.

The GraphQL backend implementation is provided by the wonderful people over at Juniper. I have already used Juniper in other hobby-projects and because I liked it then, I used it again. It makes the GraphQL integration into Rust very smooth.

As it is often the case in my funny little coding adventures, Juniper is a crate with a not-stabilized-yet interface. From time to time, they change some macro syntax to improve the ergonomics and also keep everyone with a dependency awake and entertained. But again, I can take this with a smile because it is all fun for me!

Using a GraphQL interface allowed me to decouple development on the backend and the frontend a lot. This might be more important for large teams, as opposed to me running a one-man-show. But it is always nice to have a clean interface that decouples services. For example, when I change the fields I want to read on a specific request, I only have to change the frontend code and the backend code remains untouched, provided the fields already existed in the abstract view.

Important to mention: This node is only allowed to read the database, not writing it! Of course, it would be possible to do mutations over GraphQL. But that is mostly only useful when the client directly changes entities of the database. In the case of Paddlers, the client never performs direct data manipulation. It only requests to update the database with a set of fixed API calls. And that is tightly bound to all kinds of logical checks which I did not want to include in the GraphQL node. The Game Master node (discussed later) already does similar checks, so I thought it makes more sense to put the write-API there.

Speaking of the database, I heavily rely on an ORM called Diesel. I use it to build SQL queries in Rust which are then type-checked by the compiler. If they don’t match the actual tables on the PostgreSQL database, it won’t compile.

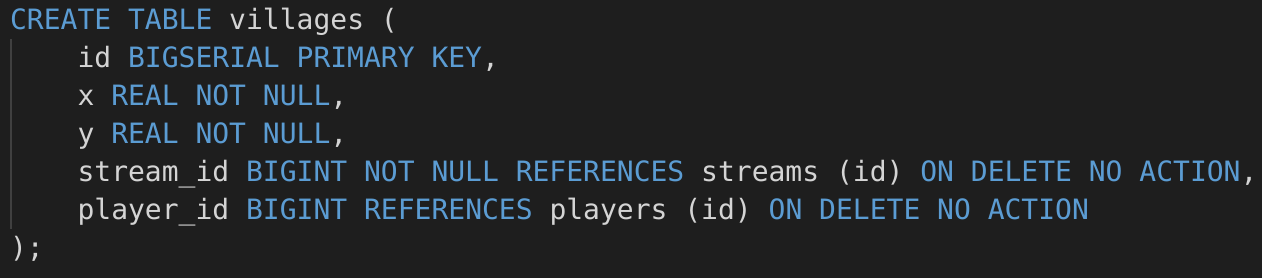

Yes, thanks to Diesel, the Rust type-checker can absolutely guarantee me that my SQL queries are type-safe! Well, almost absolutely. To build the tables, I still have to write SQL CREATE TABLE queries by hand.

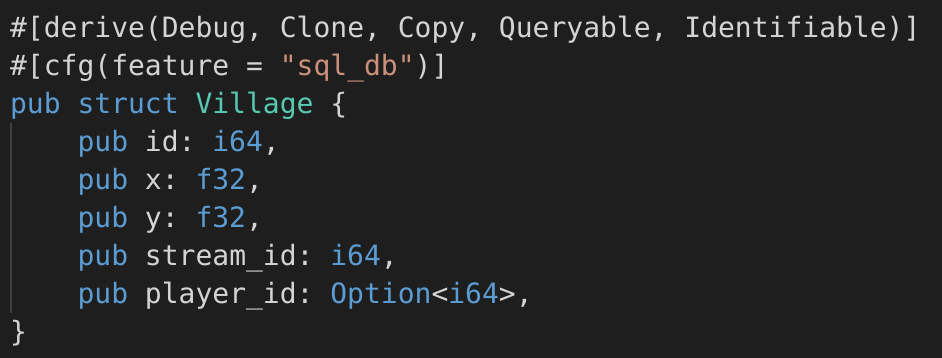

This creates the table for Paddlers villages. Each village has integer coordinates and a corresponding stream that it is attached to (all villages must be close to water). The reference to a player is nullable because not all villages must be owned by a player.

And then I need to write Rust structs by hand with the correct types and annotations to match the tables created by my SQL code.

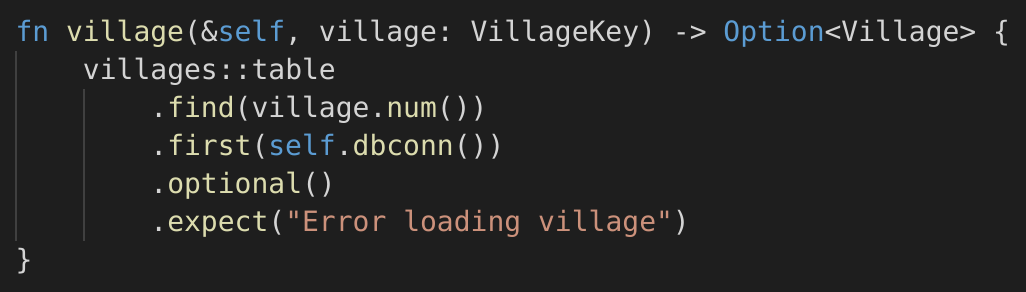

But then I can run queries like this:

This function takes a village primary key and queries the villages table for it.

It starts by building a SELECT query on the table villages and adding a WHERE clause to it by using its primary key.

With first(), the query builder is terminated and the query gets executed, returning a Rust Result that either contains a single row represented as Ok(Village) or an error.

The optional() call then transforms an empty query result into a Rust Ok(None) while other errors are preserved.

As a reader, you might be used to having good ORM support in more mature languages like Java, PHP, or C#. But I think with Diesel, Rust is not too far behind in that regard. If you are looking for an ORM in Rust, I definitely recommend Diesel. It has been stabilized in early 2018 and has an active, great community.

Another big shout-out goes to the contributors of Rocket, the HTTP server I used for the GraphQL node. They have created an incredibly simple framework with outstanding documentation, even for Rust community standards, which are generally already high.

Rocket also gave me an excuse to use the nightly Rust compiler for my projects with all the awesome cutting-edge features that haven’t been stabilized, yet! I’m not even being sarcastic here, hands-down, there are many great features in the pipeline which I like to use but are not available on stable Rust, yet.

But back to the point, Rocket only works on nightly Rust, which unfortunately renders it unusable for some projects. Not an issue in my project, however.

Also, I have used Rocket for several other mini-projects already and I think it is mostly stable. I only had a breaking issue once and only for cross-compilation of an external dependency for cryptographic computations (ring) which itself works on stable rust, so it was not really an issue of Rocket itself.

Game Master

The backend service that actively changes the game state is named Game Master. It is responsible for two main things. One, update the game’s state according to the universe’s rules, such as moving objects or spawning units. Two, reacting to API calls from the players.

For the API calls, I went with an old-school HTTP interface that more or less follows the REST principles (no GraphQL here). Authentication and authorization are handled using a JWT token, handed out and signed with RSA by the Keycloak node. The client has to send that token alongside each request.

I didn’t mention it before but these same tokens are also used at the data interface when accessing a player’s data which is not public. But other data, such as village positions, is public and reading those fields requires no JWT token.

To implement the API interface, serde and an HTTP server is all I needed in terms of library support. For the HTTP server here, I didn’t go with Rocket because I wanted to try something new. So I used actix-web which builds on the actor-based framework actix. It features the actor-oriented software paradigm and is described by the maintainers as “rust’s powerful actor system and most fun web framework”. Reading this, I just had to buy in!

Using actix-web, I was a bit disappointed that I didn’t actually need to write any actor-like code. It was all well-abstracted away and quite intuitive to use. Feeling betrayed, I decided to implement the rest of the Game Master using the actix directly. This way I hoped to learn some more about the concurrent computation model that represents an alternative to threads.

As far as my understanding goes, actor-based programming promises lower overhead compared to threads but requires rethinking everything related to the program-flow and program-state. In other words, you have to rethink everything

I didn’t push it to the limits, yet. But so far, actor-based processing of regular tasks such as Mana regeneration or health-computation (happiness in Paddlers speak) worked quite fine for me. However, I must admit that right now my code is hardly actor-based. Sure, I implement the Actor trait for my structs and integrate it all such that it works. But at some point, I realized that I pretty much eluded the core principles of actors.

For example, my actors right now just block their thread when they connect to the database with Diesel. I did that because I had read that there are no asynchronous database drivers for PostgreSQL that I could use with Diesel, so I thought I have no choice but block. In hindsight, I could have easily worked around that by setting my workers up differently and making use of Rust’s futures to deal with the asynchrony. I hope I will find the motivation one day to fix this and move to a proper actor-based model.

About my impression of Actix, I think it is a cool library and the community seems to be very active. The written documentation looks amazing at first glance and lured me in quite quickly. Sadly, it is far from complete and I would recommend everyone who starts using it to look at the code examples and the source code docs to get a complete picture. Only then you do have a chance of finding out about all features of Actix.

Rust everywhere

One of the cool things about using Rust code everywhere is that I can share code among frontend and backend nodes. This is especially useful for the type of business logic that has to be computed by both client and server.

Take, as an example, the code which checks if all conditions are met for a worker unit to start cutting wood. This involves some position checks and summing up the forestry capacity of the village. First, this check should be done by the client when the user right-clicks on a tree before sending a request to the server. But the server also needs to verify the validity of the request.

If, say, I had written the frontend in JavaScript and the backend in Java. Then I would have to write and maintain my code twice in two very different languages.

In my case, this code is placed in a library crate which is shared among the backend and the frontend. The exact same source-code is used by the server when it validates the request as the client does while executing in the browser. I only have to write it once and maintenance is also easier.

A similar benefit arises in the context of network communication. In general, when sending an object over the network, it is serialized at the sender and deserialized to some other object on the other side.

In a typical distributed system, the two nodes can be written in different languages. Therefore, object definitions must somehow be generated from a specification (e.g. GraphQL). Or sometimes, perish the thought, this is manually kept in-sync by eager programmers.

In Paddlers, the struct is the same on both sides and it is defined only once in the shared library. A lot of headaches gone right there.

IP and HTTP connectivity

To complete the technical overview, I will also talk quickly about the networking infrastructure.

The reverse-proxy setup pictured above is actually only a week old. Now, thanks to the reverse-proxy, the Game Master API is accessible at demo.paddlers.ch/api/. Before, each service had its own public entry point served under different subdomains, for example, demoapi.paddlers.ch/ for the Game Master.

The old setup would have allowed for complete decoupling of the different services’ locations. For example, I could keep the Keycloak application server and database with the user data on a trusted private server in Switzerland but move the Game Master service to Amazon (AWS) or Microsoft (Azure).

The main reason why I moved away from the initial design is that I have now added SSL. Keeping the old design would have lead to a lot of overhead. For example, a client would need to create a separate HTTPS session for each of the services and I would also need to maintain several SSL certificates. This is despite the fact that now everything is hosted in the same environment anyway.

Furthermore, I have been able to remove some annoying issues around Cross-Origin Request Security (CORS) by adding the reverse-proxy.

Because all services were served under different domains, the HTTP requests performed by the WebAssembly code were headed to foreign origins. Following CORS, the browser had to send an OPTION request first to ask the service if this cross-origin access is intended.

As a result, I had to configure both my Rocket HTTP server and my actix-web HTTP server to accept the origin I expected the client to use. Which origins should be accepted varies between environments. When testing locally it is different from the online demo. And locally I even have three different testing setups, to also test from my phone for example.

Against my will, I spent quite some time to make sure this configuration worked in all environments. That was annoying work, and the resulting code was quite ugly. Naturally, I was very happy to delete all that code!

Closing word

Puh, that has become longer then I anticipated. Turns out, running a real-time massively-multiplayer game in the browser is not technically trivial. But now that I have a large part of the infrastructure up and running, I hope I can start adding more of the core features and make Paddlers an actual game rather than just a bunch of code.

And that’s pretty much it for today. I hope I could give you an idea of the biggest technical pieces and how they work together.

Thanks for reading and joining me on my coding-adventure!